Freelance writer, editor and soon-to-be-published novelist Kirsten Krauth recently tagged me for the “next big thing” meme that has been doing the rounds of Australian literary blog-types.

Ah. Meme. That’s a word that takes me back to the days of Dreamweaver (I was never hardcore enough to handcode) and learning Director. Yes, there was a time when we thought cd-rom was going to be the new standard for digital writing. Daggy words like hypertext, interactive and digerati come to mind, though I still think Linda Carroli‘s pretty rad. The Oughties seem as long ago as the Nineties, in some ways.

Meme was pretty hip as a term then for the viral spread of cool_shit. So meme me up, Scotty.

The brag of “the next big thing” is that I gets to tell you what I’m working on, all bright and shiny and new. Not to me, of course. Working on Splendor is like looking at a Mona Lisa tea-towel I’ve been washing up with through fifteen years of share houses. It’s a good tea-towel so I’m not going to stop using it, but I don’t talk about it much.

1) What is the working title of your current/next book?

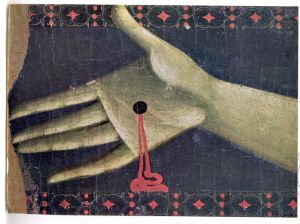

Splendor. This is not quite splendor in the modern sense (nor an 80s sugar substitute, though that always pops into my head) – it’s more than magnificence. The title is a reference to the medieval painter’s understanding of optics and the multiplication of light from a gilded object. Before artists wanted to paint people they painted the divine, and that meant MAJOR bling.

2) Where did the idea come from?

I took a pain-in-the-arse journey in the freezing cold in 1997 to see the cycle of St Helen by Piero della Francesca and discovered why you should never travel Italy in winter. It was closed for restoration. In a little church down the street I was completely blown away by a work by a medieval artist I had only vaguely heard of, named Cimabue. He’s a bit of a phantom – his surviving works are few and mostly wrecked. The crucifix in question was grimy and poorly lit (since restored) but it was poppingly different to everything else of its era. A gruesome, dead body hung there, flesh hanging away from the bones of his face. I discovered later that Francis Bacon admired Cimabue and you can see why – the expressiveness of his work was completely new.

So that led me to ask the questions how and why – what would make a painter step away from his taught traditions, when no one ever had before? And how could he and did he develop a new method of putting paint on, and more mysteriously, seeing? Painters were about as innovative as bookbinders, and painting was considered a grunt craft, very lowly. Cimabue painted a long time before the rockstars of the Renaissance – the concept of the individual was barely nascent in his age. I considered what kind of a man Cimabue might have been, and where he would have come from. And then I had to find a way to write about painting that wasn’t about seeing but experience.

3) What genre does your book fall under?

Literary historical fiction with a dash of meta.

4) What actors would you choose to play the part of your characters in a movie rendition?

I don’t know about filmability, though The English Patient used the frescoes by Piero that I managed to miss seeing at Arezzo in 1997 to swoon-worthy effect.

The modern-day protagonist (the book has a split timeframe) Pan needs to be sweet enough to attract trouble but also bookish – Abbie Cornish seems perfect.

The modern-day protagonist (the book has a split timeframe) Pan needs to be sweet enough to attract trouble but also bookish – Abbie Cornish seems perfect.

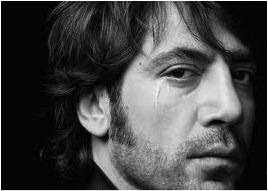

Cimabue I can only see as one actor – leonine, capable of great quietude but with a chef’s temper. Javier Bardem.  His looks don’t hurt either.

His looks don’t hurt either.

5) What is the one-sentence synopsis of your book?

A woman whose hands tell her secrets, her obsession with a medieval painter, and the hunt to find him.

6) Will your book be self-published or represented by an agency?

An agency is my preference. Now that I’ve found out the next Dan Brown is on Dante; they’ll be knocking my door down, right?

7) How long did it take you to write the first draft?

Er. Coming up on twelve years. In my own defence there has been a lot of life, and another novel, in the interim.

8) What other books would you compare this story to within your genre?

Probably a little bit Tracy Chevalier’s Girl with a Pearl Earring tupped by Peter Robb’s M, then reputation restored by Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall.

9) Who or what inspired you to write this book?

Once I started digging, the circumstances of Cimabue’s work, and his time were just too good NOT to write a book. He’s thought to have been master to Giotto, was contemporary with the first flush of poetry that made Italy great (Dante, Cavalcanti etc), and right there on the biggest art commission of the epoch – the church of St Francis at Assisi.

This might not seem so sexy but St Francis was popular beyond what I can describe – imagine him in Who magazine every week for a hundred years. Canonized almost immediately when he died, an unstoppable wave of people devoted themselves to his philosophy and example, and his order commissioned art of great beauty in huge quantities. He was a cult figure who inspired people to incredible change. And Cimabue was the first artist given the job of decorating the place where the body of the saint lay. Ka-ching!

It’s also set just before the plague hits Italy, which is nice.

10) What else about the book might pique the reader’s interest?

Like Thackeray’s Barry Lyndon, it’s a good tale because it’s a rise and fall. The historical Cimabue was a victim of his own success. His experiments with paint meant lots of his work went black, and his pupil Giotto became so stratospherically famous in a generation that his teacher was utterly eclipsed. Cimabue soared, he crashed, and Dante wrote him into the circle of purgatory with the prideful. But his last works are very beautiful; he’d learnt a lot.

Pan thinks she’s pretty damn special too, hunting Cimabue down like some maven looking for rare vinyl. She has a gift that takes her beyond the norm, a supernatural version of “the eye”, as art connoisseurship is known. She sees things in art that are hidden to most people but still manages to be a total donkey about life as it is lived. She might learn to leave the historical record alone for a damn minute and find some fulfillment in the present. She’s due for some falling of her own, via misplaced pride, lust and falling for flattery. Isn’t that what your twenties are for?

But that’s not where this meme-y thing ends, oh no. You’ve got to go and visit some other writers that will put you ahead of the curve like a steamboat dinner party in the 1970s. Rat-tail hair in 1982. You get it. This is a slight problem as my personal reading of the last year has been mostly on the contemplation of God in the 1280s – and I’m not pointing you in that direction, because I like you.

Still, I do heartily recommend you visit:

Jon Bauer – compelling, likeable writing, no sorry, just a momentary lapse, actually dystopian and creepy in the best Russell Hoban manner. Current works may induce paranoia similar to that Northern Lights stuff I got given in Amsterdam but you’ve been warned and that’s not going to stop you from trying it.

Tim Denoon – Tim and I had the good fortune to go to Varuna, where lucky authors go to be fattened, in 2011. He’s writing something very good. George Saunders via Chesterton with a touch of Sedaris? Or just Denoonian?

Tom Cho (who won’t be meme-ing his project because he’s gallivanting the world writing it) but his collection Look Who’s Morphing is satire worthy of Swift if Swift watched a lot of PopAsia and liked eating Haw Flakes. His current project is deep, but he’ll flash-fry the philosophy to make it tasty.

Marguerite Yourcenar. She’s not local. She’s not even alive. But she’s given me the most profound reading pleasure and philosophical food in the last two years. She was dead before memes were invented but you should read her. Essays, novels, memoirs. All stellar.